Words by Shawn “Speedy” Lopes

Photos courtesy of Gary Chun and George F. Lee

Stepping into the raunchy old cabaret, I felt a strange mix of excitement, wonder and apprehension coming on. Dark, squalid and frilled with garish drapery decades removed from good taste, it smelled of generations of cigarettes and stale beer.

I’d found Club Hubba Hubba a perfect match to the venue of my imagination and entering my first nightclub — Honolulu’s most notorious strip club, no less — was an adolescent thrill of the highest order.

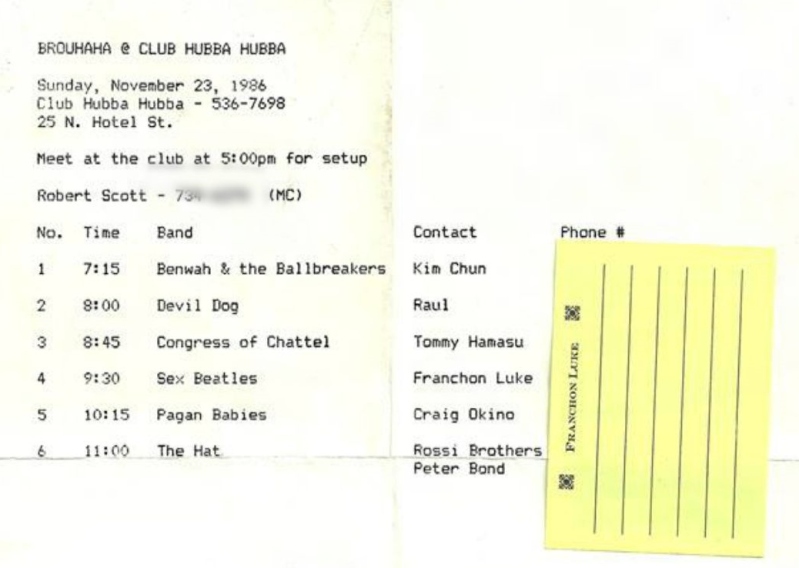

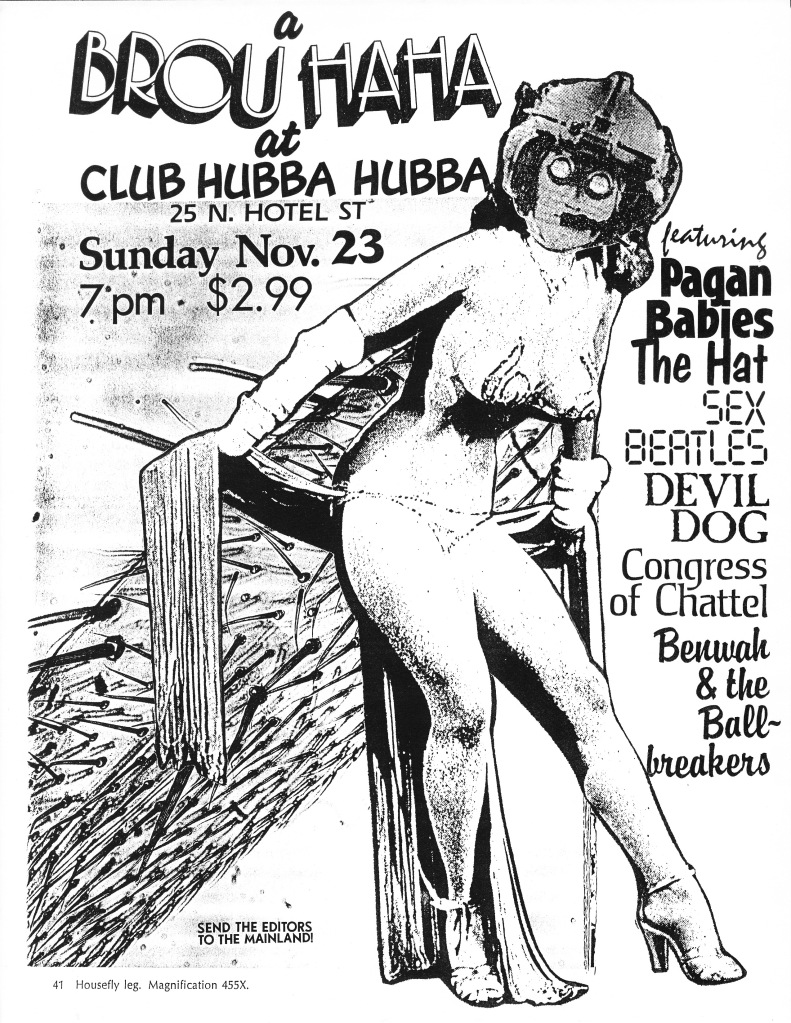

I was underage. Normally, I wouldn’t have been allowed in (some might argue otherwise), but this was a special occasion: a live, loud and raucous music bash for the infamous Brouhaha fanzine was taking place. Of all the local ‘zines that were passed around at the time, none had quite the reach or influence of Brouhaha and few could command such a riveting lineup of Hat Makes the Man, Pagan Babies, Devil Dog, Sex Beatles, Congress of Chattel and Benwah and the Ballbreakers.

It was a hot mess of a show. The bands, having commandeered the stage for the evening, effectively gave the strippers the night off, save for one kind soul, who, in between sets, charitably shed her outfit to bobble a pair of strategically placed pasties for the crowd.

The tales of that night have since spun into legend, but the story of Brouhaha and its tidier, more ambitious predecessor, Novus, begins much earlier. In fact, you might go as far back as the late 1970s, when Burt Lum, then a student at Stanford University, manned a radio show at KZSU, playing jazz and Hawaiian platters. Falling in with a broad-minded set, he took inspiration in the wondrously vital punk and new wave scenes in nearby San Francisco. “It was kind of an introduction to the whole vibrant youth culture in the Bay Area,” explains Lum. “Stanford’s just south of San Francisco, so up in the city, that’s where a lot of stuff was happening.” There were infamous shows by Dead Kennedys, Crime, Flipper and Pearl Harbour & the Explosions, all documented in fanzines like Search & Destroy, Maximum Rocknroll and BravEar in the early days of SF punk and alt rock.

Returning to Honolulu in 1981, Lum found a blossoming music and arts scene had also sprung up in his own back yard. Not only were the bands more plentiful, but the types of bands were more varied and interesting than he remembered. Musically progressive clubs like 3D and Wave Waikiki had already set up shop and a new generation of nightlifers had begun to descend upon Honolulu, though you wouldn’t have known it by following the local media, who were still behind the times when it came to chronicling such trends. ”There was so much out there that it was hard to describe just the nature of the contemporary scene,” remembers Lum. “It wasn’t really getting exposed. If you had to rely on the radio here, there was nothing; it was still pretty much Top 40 stuff.”

It’s a sentiment echoed by Gary Chun, a scene veteran and voracious consumer of music. By the time he’d crossed paths with Lum in the early ‘80s, he had already caught several now-iconic bands of the new wave, long before most had even heard of them. In 1979, Talking Heads, though far from a household name, had just experienced a spike in popularity through national spins of “Take Me to the River” and were brought in to play Little Orphan Annie’s, an airport-area watering hole just a stone’s throw from Hickam Air Force Base and Pearl Harbor. This was followed by an historic, though under-advertised show by the up-and-coming B-52s, only months later. As Chun recalls, the tiny B-52s crowd at Annie’s was “just a bunch of us, all up front, who knew of the band — a very small number. I’d be surprised if they got 50 people in attendance. The military guys in the place were just wondering, ‘What the fuck are these guys?’” He shakes his head at the memory. “I’m sorry I don’t remember who promoted those shows, but they had great foresight.”

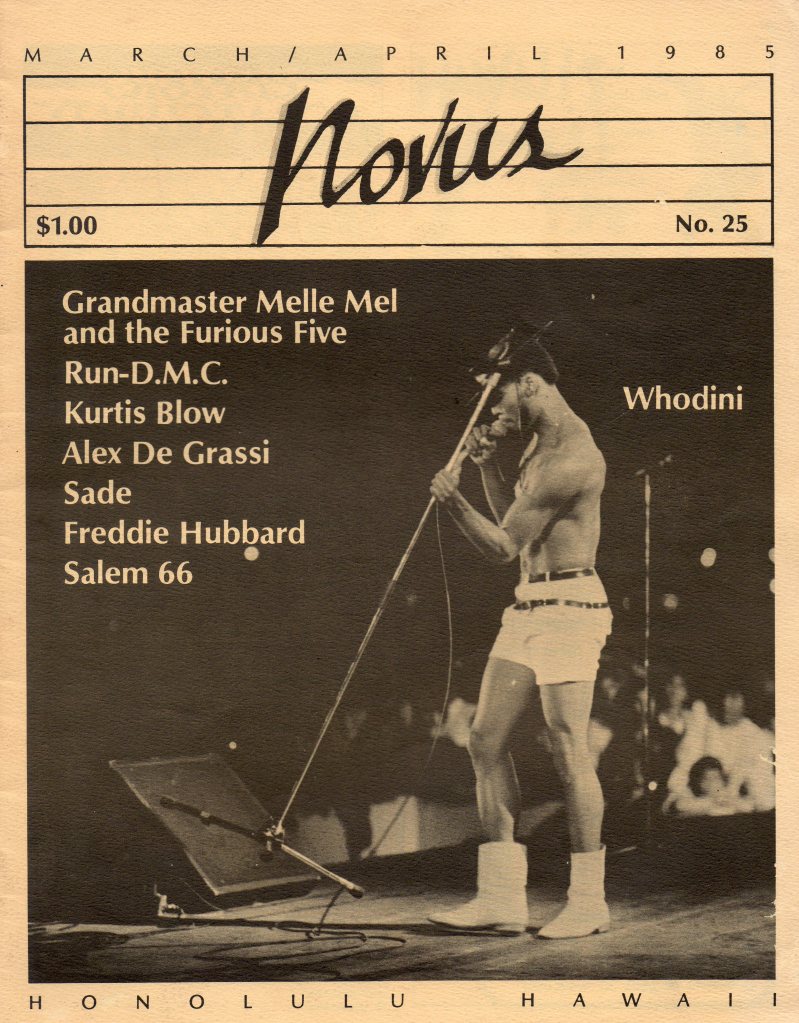

Perhaps it was destiny, but before long, Chun and Lum, eager to report on the growing local scene and the new seismic shift in music, established Novus. When it premiered in the fall of ‘82, hip hop had started to make serious incursions into radio, the British synth-pop invasion was in full swing, Hawaiian music had begun to branch out into new musical territories and reggae’s annexation of the Hawaiian Islands had already taken root. Lum would be editor and Chun associate editor. They soon created a radio show, christened Rough Take, which aired on the University of Hawaii’s KTUH, to promote the magazine and provide an aural component to Novus.

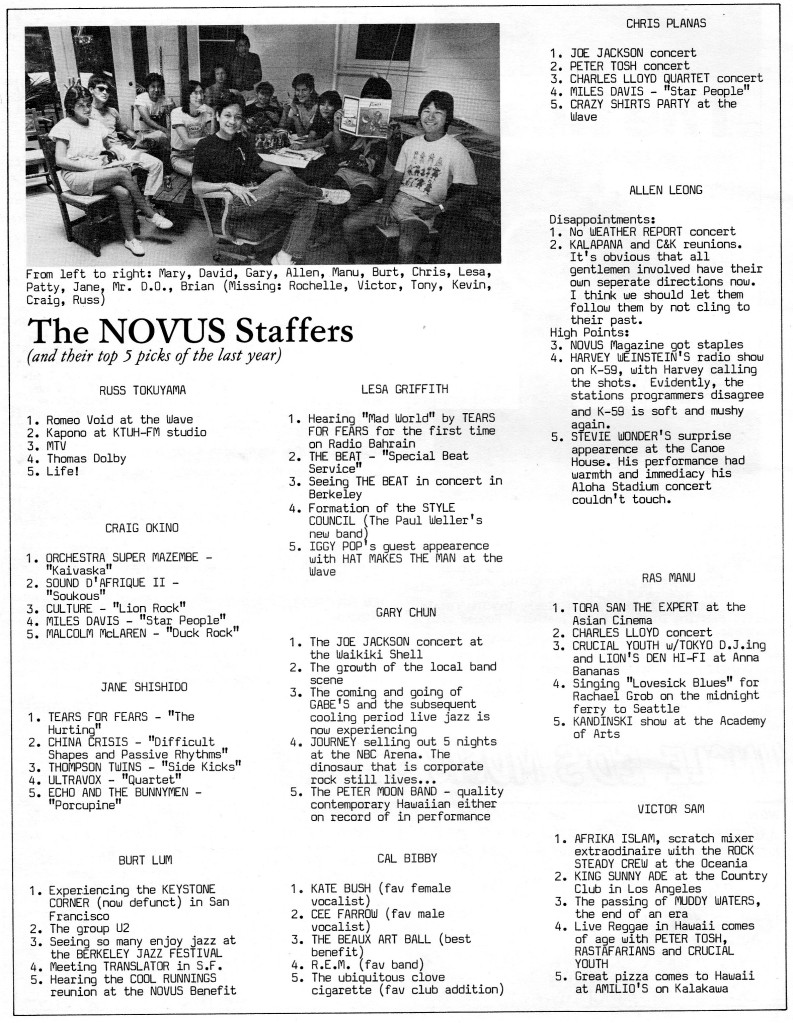

Prepared to commit countless hours to their promising new enterprise, the duo still needed input from other writers, designers and photographers to satisfy monthly deadlines. “When you build community, certain people kind of pop up,” states Lum, recalling his search for a talented staff. He fires off a list of trusty contributors who were keen to join the cause: “Allen Leong, Jay Junker, Chris Planas, Lesa Griffith, Victor Sam. I approached them to see if they’d be interested in writing. These were people that were self-motivated. I mean, I’m not paying anybody. My thing was to try to just get this thing together.” Lum even obtained the services of a mystery photographer, already employed by one of the major newspapers in town, who nonetheless shot for Novus under various pseudonyms.

“Of all the writers, I was probably the oddball and least productive,” quips Sam, who was recruited by Lum and Chun while volunteering at KTUH. A California transplant with an ear for the offbeat and radical, he wowed the pair with accounts of his pilgrimage to New York City just a few years earlier, in which he took in shows by boundary-pushing jazzmen like James Blood Ulmer, Sun Ra and David Murray. It was thought his involvement could give Novus a certain post-modern edge. “I was interested in what was happening in New York then that wasn’t being written about on the West Coast and certainly wasn’t being written about in Rolling Stone,” Sam recounts. “I asked Burt ‘You mind if I write about this kind of stuff?’ Burt goes ‘No. In fact, we might be able to get it for you for free.’ Really? I was thinking ‘This is kind of cool.’“ The free promos soon came, then the reviews for Praxis, Bill Laswell and New York hip hop and electro beatsmiths like Afrika Bambaataa, Grandmixer D.ST and Divine Sounds.

Griffith, along with fellow contributor Tony Dela Cruz, penned a music column for Ka Leo O Hawai’i, UH’s student newspaper, when both were brought into the fold and given the freedom to pursue their passions. “It was just so neat how Burt brought all these people together,” says Griffith. “Burt’s such a good cheerleader and a real nurturer. He totally indulged me. I’d draw a picture of Paul Weller and he’d put it in there,” she says, laughing at the recollection.

A self-confessed “rabid fan of British pop”, Griffith rummaged through the bins at local record shops to find the latest import singles to review. Then she’d peruse the trendy music mags for leads. “I’d go to Jelly’s, get my copy of The Face or New Musical Express, read it cover to cover a hundred times and if Jelly’s didn’t have what I wanted, I’d order records from the UK with my hard earned pennies from my UH student job,” she reveals. “I was lucky that my dad worked for Pan American airlines and I could fly for free, so in the summer, I’d even fly to London and see shows and buy records and clothes.”

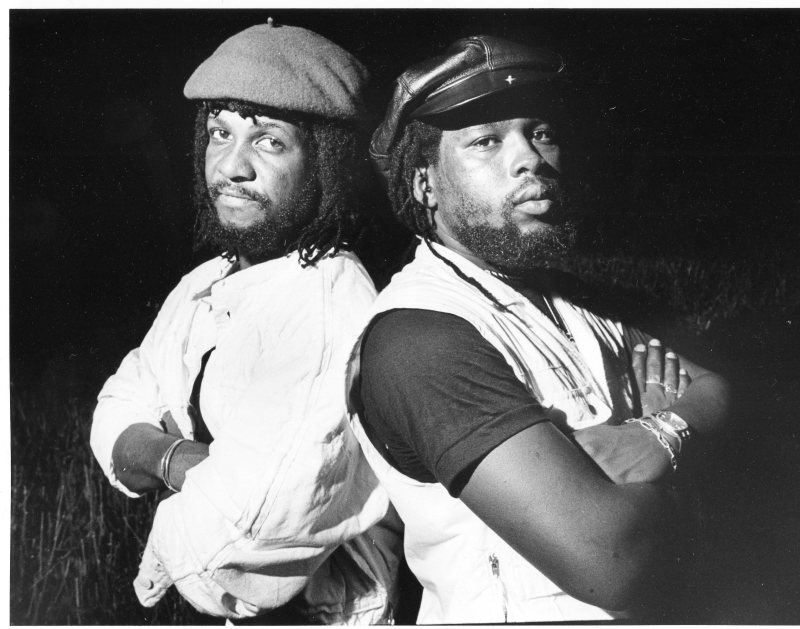

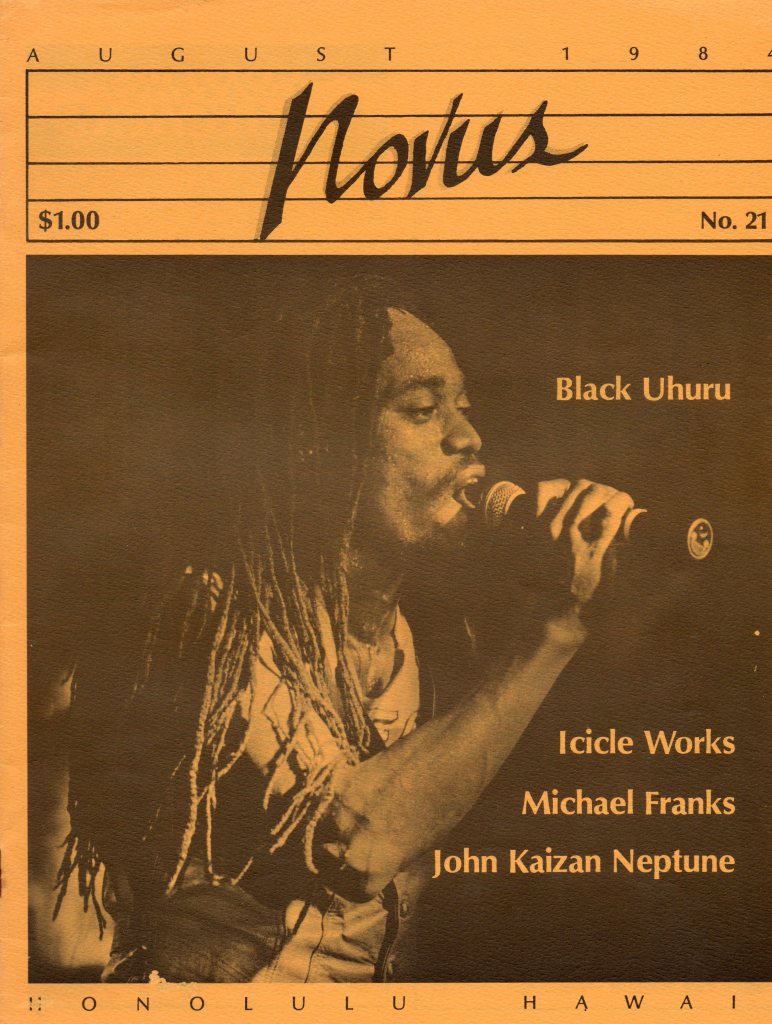

Between 500 and 1000 copies of Novus were printed each month, initially free to readers, who found it at places like Jelly’s and Tower Records. Subscriptions could be purchased for a nominal fee. Even early on, they’d managed to produce cover stories and interviews with The Pretenders, Grandmaster Melle Mel, Peter Moon Band and Black Uhuru, to name a few. It featured scads of reviews.

Novus was a toilsome undertaking, to be sure. In the days before publishing programs, churning out a magazine often meant cutting out pieces of typewritten paper and pasting them manually on a gridded layout board, in columns. The layout would be taken to a printer, who then created a print-ready image of it before going to press. “If you think about it, it’s pretty archaic,” notes Lum. “My writers would give me stuff and I would sit there and type it, and if I made a mistake, I would have to retype it. There was no copy-and-paste function.” He eventually dumped his electric typewriter for a Kaypro home computer with Wordstar word processing software, which was state-of-the-art at the time. “When I saw it, I just thought, ‘This is unbelievable. I can type stuff in and I can edit it and print columns for my layouts. Wow, this is amazing!’”

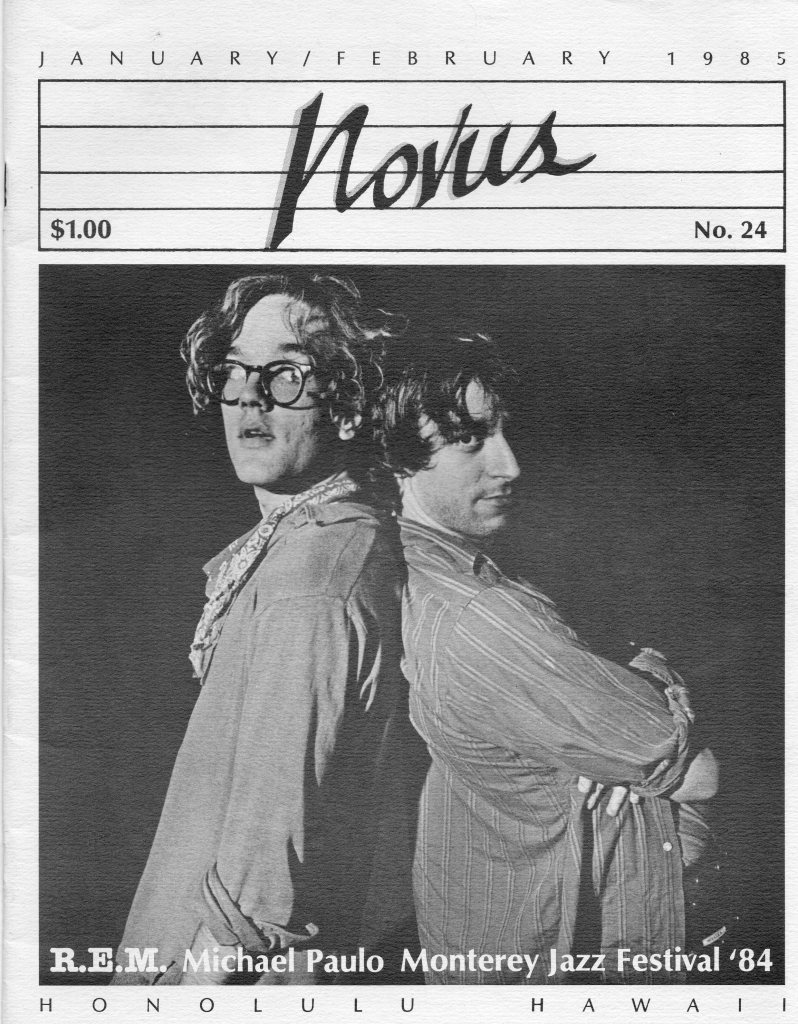

As the renown of Novus grew, the stories got bigger. There were interviews, features and meet-and-greets with U2, R.E.M., Wynton Marsalis and Red Rockers. The Novus crew were even invited to a closed, industry-only CBS convention in Waikiki in which Sade performed its one and only show in Hawaii. “I wore my black ski pants and my black turtleneck and set up by the stage,” gushes Griffith at the memory.

But nothing lasts forever, and as they say, life happens. The writers, who for years had so selflessly donated their time to the project, still had lives to lead. Some fell away, some moved off-island. Business costs rose. By the latter half of the decade, Lum had come to a crossroads. Tough decisions had to be made. “At some point,” he concedes, “Novus just sort of outlived its passion.” He’d always pondered taking Novus to the next level. The problem was that getting prominent advertisers on board with a sleeker, full color magazine would require not only increased dedication from all involved, but a decidedly larger paying readership, which he could not guarantee.

“So you can choose the glossy route, but it compounds the challenge you had just as a small magazine because everything multiplies in terms of expenses,” he explains. “Then you’re chasing a number. How many subscribers do you have? How many readers do you have?” More importantly, it would have taken away from the original grassroots nature of Novus, which Lum found difficult to surrender. He had a better idea. If printing was his costliest expenditure, why not keep it to a bare minimum? Why not devolve the entire process into something more sustainable? “So what I did was I told everybody, ‘You can all still be a part of this project, but instead of giving all your stuff to me and having me lay it out and paying a printer, why not everybody just produce their own page?’”

And with that, Brouhaha was born. New contributors signed on. Each was given free reign over a two-sided page, which, when amassed with the works of other contributors each month, would constitute a new Brouhaha issue. There were poems, reviews, illustrations and bizarre cut-and-paste collages. From the outset, Brouhaha was a disorderly pastiche; a cacophony of images, ideas and opinions, all completely untouched and unedited. As Lum says, “It became very organic. We went from having a table of contents, a well-formatted masthead, columns and bylines with Novus to the opposite direction with Brouhaha, which was more chaotic, more anarchy. And in a way, I kinda liked that. It was more gritty.”

For a while, says Lum, publishing was enjoyable again. “I’d have Craig Okino from Pagan Babies lay out some crazy collage. I remember doing midnight Xerox runs and we’d get together and have collating parties. Those were fun. There’d be like, ten of us, sitting in a room and we’d have the music going, passing one page to the next guy, then glue the binding together.” Brouhaha also put on live, free-for-all events with local bands. The party lasted three more years, taking it to the far edge of the ‘80s. “Novus was a labor of love, but Brouhaha was even more a labor of love because there was much less revenue coming in,” he reasons.

Eventually, the same problems that arose with Novus appeared with Brouhaha. Adult responsibilities overruled all, and by the close of the 1980s, Lum had ended his publishing run. “I came to the realization that we could just do it for fun, but at some point, you gotta make money, you gotta focus on priorities. We did what we wanted to do and we kinda moved on.”

Planas, Sam and Leong relocated to the Bay Area. Chun became an entertainment writer for the Honolulu Star-Bulletin and Star-Advertiser. Griffith’s resume grew to include writing and editing jobs on the East Coast and in Europe, highlighted by a stint at Time Out New York and editing positions at the Honolulu Weekly and Honolulu Advertiser. Another contributor, the late Patricia Bibby, for whom a scholarship is named, went on to become a UPI reporter and an editor and writer for the Associated Press in New York.

It was a time in Griffith’s life she won’t forget. “It was just exciting being part of it because there were a lot of exciting bands and we covered everything. The writers were on to early hip hop, they made sure Hawaiian music had a voice, jazz, even world music. There was a lot happening in Hawaii and I was a part of a little slice of it.”

Epilogue

When I first became aware of Novus, I was a mere preteen (a music-mad one at that) who picked up free copies at Tower Records whenever I earned enough allowance to stop in for a cassette or LP. By the time it morphed into Brouhaha several years later, I had grown crafty enough to sneak out of the house and attend Brouhaha shows on my own.

In time, I would come to know some of the writers as an adult. While jobbing at Jelly’s, I’d encountered Victor, who often popped in to browse for new music. In 2001, after freelancing for the Honolulu Weekly and Honolulu Advertiser, I’d secured a part-time position at the Honolulu Star-Bulletin, where I found myself working alongside Gary, often writing about music. I would leave the SB in 2004 to pursue another dream of mine, which was to open Stylus Honolulu, on which Lesa did an interview piece for the Honolulu Weekly.

But this is the amazing part. It wasn’t until after coming across some old issues of Novus and Brouhaha recently and seeing their names in print again for the first time in decades that I’d realized something about these writers — Wait a minute, I know them! Mind blown. I was determined to retrace the story of Novus and Brouhaha and speak again with the people who had inspired me all those years ago to become a writer. It’s not often that you get to meet your idols. I’m just fortunate to have known mine all along, whether I realized it or not.

Thanks for the history lesson, Shawn! Tell Gary Chun, I’m still a big fan!

LikeLike

I will. Me too!

LikeLiked by 1 person

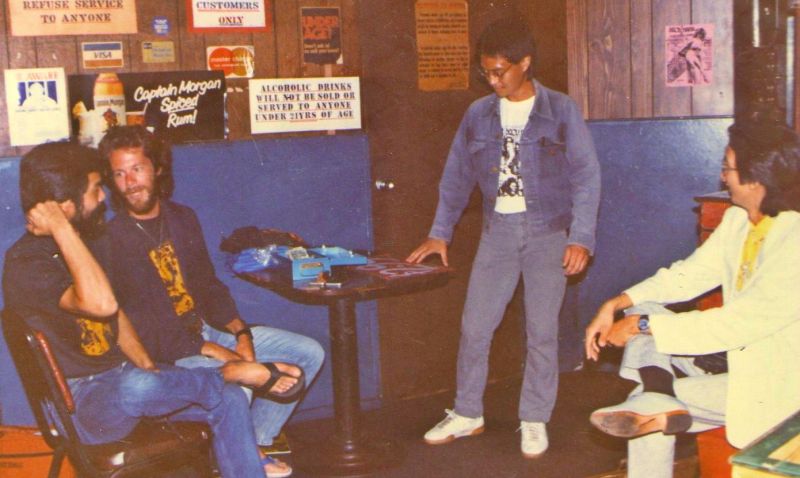

Looks like Raoul from Devil Dog in that picture.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It is, but because of the way this blog is set up, I just wasn’t able to caption the top photo.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yeah, used to see him gig at C-5 all the time. Do you remember the show that Matt put on at C-5, an afternoon all ages show called ‘Orgy of Thrash’?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think BYK might have played that show….

LikeLiked by 1 person

I never went to C5. Heard lots of stories, though!

LikeLiked by 1 person

C5 & 3D, a couple of my favorite clubs in Hawaii!!

LikeLiked by 1 person